Since the disappointing pricing at the 1.1. renewal the bad news on reinsurance pricing has kept on coming. April, June and July renewals were all reported as materially down by the major brokers.

S&P adopted a ‘negative trend’ in its reinsurer ratings in direct response to the January outcome, Moody’s followed with a ‘negative outlook’ for the sector last month. Best and Fitch by contrast maintain ‘stable’ outlooks but both are flagging the potential impact on sector ratings if the current environment persists.

However since the start of the year we have seen no reinsurer downgrades (using S&P’s ‘Top 23 Global Reinsurers’ as our peer group) or even negative changes to individual rating outlooks by any of the agencies. Indeed, while most ratings assessed this year so far have simply been affirmed a few have even seen upgrades or positive outlook changes.

In no small part that’s explained by much of the cause of the pricing problem; excess capital, combined with a generally positive view from the agencies about the robustness of the sector’s risk management capabilities.

But all agencies routinely stress that their ratings are prospective and that forecast earnings quality (profitability and volatility) are central to that.

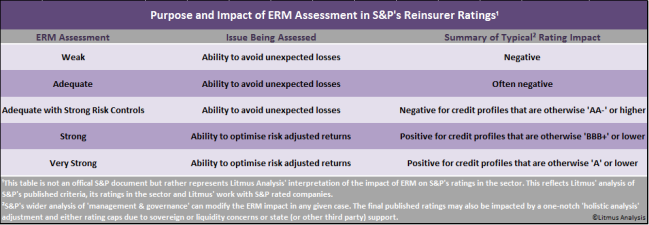

S&P’s detailed rating criteria highlights the point. Its capital adequacy model reflects a two-year forward view (currently the base case model is for 2016 in a reinsurer’s S&P rating), therefore critically including forecasted retained earnings. In addition its analysis of a rated reinsurer’s ‘operating performance’ reflects the current and subsequent year forecasts, ‘ERM’ focusses heavily on risk adjusted pricing controls and its ‘management & governance’ analysis hinges in no small part on a reinsurer’s ability to effectively set and deliver on financial targets. Added to this is the need for Cat exposed firms to ensure they do no stray outside of their ‘risk tolerance’.

Best’s too uses forward looking capital models and prospective earnings as a central part of the ratings process.

However, among S&P’s list of 23 all but 2 have already had their ratings at least affirmed by either S&P or Best’s since January. The 2 are Lloyd’s (currently a positive outlook from both agencies) and SCOR (currently a positive outlook from S&P and stable from Best). Individually S&P has yet to report on only 7 of the 23 so far this year, and Best on 10.

So, why is more rating pain not being felt?

The answer may come from how much actual earnings deterioration the agencies are so far forecasting. Again these days S&P is the most explicit about that.

Other than for the short-tail Cat specialists, in its recent rating updates the agency is typically forecasting ‘95% or better’ combined ratios this year and next. Generally that’s only a few points worse than 2013 and similar to (and sometimes better than) 2012. These forecasts assume a normal Cat year for any given reinsurer’s portfolio. (The Cat specialists of course generally operate with much lower combined ratios in a non-Cat heavy year).

Of course not all of the 23 are ‘pure play’ non-life reinsurers. Nonetheless this seems a tough circle to square with the headline pricing noise. Of course rate reductions can take a while to work through into quarterly or annual results but – given normal loss experience, and absent substantial further reserve releases – numbers reported by at least early 2015 should be expected to reflect the current pricing environment.

So either the headlines overstate the problem, or key metrics such as loss and combined ratios, return on revenue and return on equity may start struggling to hit the ‘base case’ assumptions the agencies have in their current ratings.

Some reinsurers are more exposed to this than others in rating terms, particularly those where the current rating ‘bakes in’ a strong prospective operating performance and even more so if current capital is seen as marginal for the rating level but is supported by assumed positive future earnings.

So far the agencies have kept their powder dry. As we’ve noted a before, it’s a tough call to take a negative rating action on a concern that future performance will worsen before seeing actual evidence that it has; but that, unavoidably, is what ‘prospectiveness’ in ratings requires.

The critical thing for reinsurers defending their rating in this context is to explain the defensive qualities of their competitive position (and the supporting ERM and other controls) to the agency in terms that reflect the agency’s criteria. When it comes to performance, credit rating analysts are ultimately interested in the ability to manage the down-cycle.

Rated companies do not always explain themselves to the agencies well. Some can rely too much on unsupported assertions of strengths and their ‘persuasive powers’, while others may simply respond to the details of the agency questions without focussing enough on addressing the underlying issue (or even spotting it).

In this environment, to mitigate their future downgrade risk, reinsurers will need to focus clearly and coherently on how, and exactly why, they are able to manage the down-cycle. A plea to the agency to ‘look at our capital and our track record’ may well not be enough.